Soundboard

The Steinway & Sons Podcast

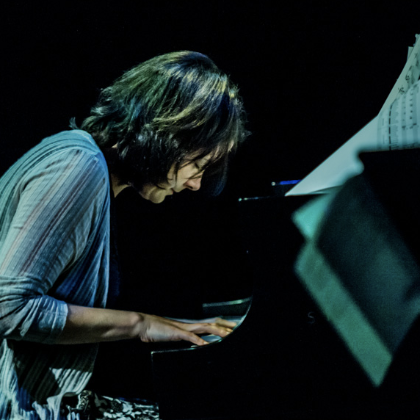

Regina Spektor

Until the Jell-o Sets

Regina Spektor on songwriting

by Ben Finane

In advance of her five-concert Broadway residency, Steinway Artist Regina Spektor talks about the craft of songwriting with Ben Finane, Editor in Chief at Steinway’s award-winning online music magazine listenmusicculture.com, at New York City’s Steinway Hall.

I don’t want to call it a retrospective, but you’re doing some shows on Broadway, playing everything.

Yeah! We’ve been calling them a residency.

I like that.

Yeah, I like it too. It’s outside of any one record. At first I started thinking, “Well, what songs work theatrically?” And then I started realizing, “Wait a minute, there are so many songs that I never even put onto albums. Let me look at all the old stuff.” And that got me into strange hours of the night, trying to figure out songs that I don’t know how to play anymore.

As a Sunday composer, this was the question that popped into my head —

Wait, what’s a Sunday composer?

A Sunday composer is a stiff like me who works for Steinway during the week and then scribbles tunes on Sunday. As a Sunday composer, I started thinking that even in my limited compositional landscape, there are works I’ve written a few years back that I don’t know where I was musically when I wrote them. So that’s my question: is it hard to find a way back in to earlier material? How do you do that?

It’s kind of strange: some of it, you just play it, and it feels so “Wow!” I feel that sometimes songs are almost like vitamins and minerals, where you’re like, “Oh, I really needed that.” And then other ones are just: “Oh, I actually never need that ever again. Ever again.” So, you know really quick. If it feels good or is surprising or somehow a new aspect comes into it, you say, “Oh, wait a minute, I’ve never done this with strings.” There’s one old song I wrote so long ago, on my second self-made record. I never thought I’d want to do a tap-dancing collaboration with that song, but I do!

So you found new entrées into old material, in some cases.

Yeah, and certain things feel really “Oh, this would be amazing with that LED wall, and with this projected on it, and with this kind of a light, and this kind of smoke — and this kind of tap dancing!”

Has this Broadway experience, let’s call it, encouraged you to think in a more multimedia way?

Definitely. I’ve had video design and projections before, but it never felt right with the touring show. One of the things that I love about live shows is that you’re not watching TV, and you’re not watching your phone. Music changed once music videos came out, and we started expecting to just sit there and take in visuals with sound all the time. And so I loved that I was just this little person at a piano, and if you were sitting really high up, maybe I was just this blurry ghost. And you could just close your eyes, or you could think about what you wanted to think about. And you weren’t being fed images of what to think about. I love for songs to be as free as possible. I don’t like to ever talk about lyrics, or meanings, or assign anything to them, other than what a person might feel or think in the moment of listening to it. And at the same time, suddenly because here’s this outside-of-my-regular-show experience and a theater residency — it’s not my touring show, and at the same time, it’s not a Broadway show — but it feels good to reimagine them with those things. So all of a sudden, it feels right for a few songs to have these video images, because it’s the theater. And so I think because of how it’s framed in my head, the song selection and the elements that we’re putting together — like scrims, how we’re going to light the string players through a scrim for this song, and then the scrim’s going to come up for this song, and then it’s going to turn all really dark and intimate for this song —

‘One of the things I love about live shows is that you’re not watching TV, and you’re not watching your phone.’

You get to add this visual element to things that were heretofore ears-only.

Yeah. And it just felt like, “Oh, it makes sense in that context!”

Let’s take it back to the music and the songwriting process. Are you a music-first person? Are you a words-first person? Do you compose at the Steinway? When you sit down and write, how does that happen?

Usually at the Steinway, and every once in a while, because of New York City living, at my little keyboard. [Laughs.] I’m a words-and-music-at-the-same-time kind of person. And sometimes, actually, for songs that I didn’t have access to a piano while I was writing — like, say I was swimming in the ocean while I was writing a song — those usually tend to stay a cappella. I think of it as Jell-O. If it sets, there’s only a certain amount of time where you could add things....

Add fruit.

Yeah, and then it just sets — and it becomes what it is. And it becomes very hard for me to change. I have a lot of friends who are so flexible: they’ll change keys of their songs. And to me, the whole thing kind of Jell-Os....

So if it’s in D-flat, it’s in D-flat.

It’s in D-flat. And that’s where the muscle memory feels it, and it won’t feel right in the hands until I find that D-flat again — even if I want to move it! [Laughs.]

Some pianist-songwriters have trouble composing at the piano because their hands fall into old positions and it feels like they end up rewriting instead of creating. Is that something that happens to you?

Oh, definitely! I’m sure it does. This really interesting thing happened to me in the very beginning, because it took me so long to even figure out that I could try to write songs. I was just playing classical music and studying classical music for a really long time, that by the time I figured out that I could try to sing and play at the same time, it was so hard for me to coordinate that I went into this very stubborn place where I felt like I had to try and free myself as much as possible, and write in all different ways, so that I wasn’t trapped in this oompah–oompah thing.

Was that a classical hangover, that oompah?

No, the oompah was that I couldn’t really do a lot of movement while singing words, the coordination. When I was just playing music, I felt like I was free. And that was one of the beautiful things that classical music gave me: the freedom of the two hands, and being able to play different lines and meters with the two hands. This great freedom. And then as soon as I started trying to sing over it, I was instantly chained to this very simplistic rhythm, because it was very hard for me to coordinate. And until I figured out how to make this band of three now — singing and left hand and right hand — work, it was really, really hard for me to get out of these very basic rhythms.

And how did you do that? Just practice? Or was there a special breakthrough moment?

It was just practice, and it was like trying every kind of thing. And then after I did that, I had this whole inferiority complex that was like, “No one is going to be able to listen to somebody play just piano and sing songs for thirty minutes! So I have to try and make all the songs sound really different from each other so that there’s contrast.” So if I arpeggiated one song, then the next song had to be super staccato. So I guess — I didn’t realize it till much later, looking back on it — but my rule was: “You’ve already written a song like this. You can’t anymore.” Because of that, that oh-I-do-this-thing-again-and-again really didn’t happen for a long time. But now, of course, that I’ve been writing songs for — I don’t know, I’m thirty-nine now, and I started when I was seventeen, so it’s been a while! — of course I end up being like, “Oh, I’m doing that thing. I’m putting my hands exactly here.” But at the same time, my voice sits in certain places, and I end up writing songs to myself where the low notes are too low and the high notes are too high. [Laughs.] And somehow I have to then figure out how to sing it. I really love being all over the place.

I think that’s something that definitely makes you unique: this expanded range, whether it’s in different voices or —

[Laughs.] Yeah. I basically — I have to try and make it work.

You say it sort of comes together at once, the lyrics and the notes. Is it a chord progression, or are you actually writing out the figures that you end up playing? Or is it just devices to remember certain things as you play it?

As I go, I think, I’m writing it and adjusting it and changing it. It kind of feels like....

Are you writing out every ornament, or do those come later as you flesh out the piece?

Usually everything. And you know what it is? It kind of feels like.... You know those stone polisher things that spin and....

Rock tumblers.

Yeah, rock tumblers! It’s kind of like if you took a rock tumbler and you slowed it down to, like, tortoise speed. That’s what it feels like.

“My rule was: ‘You’ve already written a song like this. You can’t anymore.’”

Slow grind.

Yeah, exactly! You just go over it and over and over again, till it feels right in the hands, and the words change, and then they change back. And this can go over a period of just a few hours

or a period of days or a period of weeks. But then once the Jell-O sets, then I’m stuck.

How do you know when the Jell-O sets? You just feel it? You’re like, “Yep, this is it”?

Yeah, you kind of feel it, or you try to go change that one thing, and you’re like, “Oh no, that’s not....”

And fortunately it’s not a painting, so you can actually go backwards, if you add too much.

Yeah!

I have a six-year-old. You have a five-year-old. How has that changed your songwriting? I know it upends everything, but how has that changed your writing?

[Laughs.] Well, I don’t think I’ve ever slept enough. [Laughs.] And I might never sleep enough ever again. But....

So, more hallucinatory material.

Yes, definitely! It’s definitely a little more altered-state.

Are you a post–Joni Mitchell singer–songwriter? Are we all post–Joni Mitchell, anyone who tries to come after her?

Well, this is a really interesting thing. The short answer is yes. But for me, you know, she’s very Canada, North America. And in Soviet Russia, nobody knew who Joni was. And certain things made it over there, like especially in the underground scene. I grew up listening to The Beatles and The Moody Blues even before I knew English. But really the continents upon which my music consciousness stands are classical music, or the Soviet guitar-playing singer–songwriter bards like Vysotsky, Okudzhava. There’s this whole incredible amount of these poetic singer–songwriters —

Troubadours.

Troubadours, exactly! And it’s real poetry. And it really is the part where you realize, early on, that songs could be about anything. Because these people, especially Vladimir Vysotsky, he wrote really about anything. He was an actor. He died very young. But he wrote thousands of songs. He was a national hero. And he wrote joke songs, and songs that were such incredible, vivid descriptions of things that happened during World War II that people wrote him letters. Veterans wrote him letters saying, “I was there. I was in your platoon when that happened.”

Because they thought.... Oh, wow.

Because it was so vivid. Then the next song would be from the perspective of a petty criminal. These incredible works of art that were so complete, and because he was an actor, he could truly embody it.

So that gave you the freedom to go esoteric when you wanted to, and universal when you wanted to?

Well, yeah — but! There’s a “but” there because none of them were women, and because none of the composers, the classical composers that I was playing, were women either. This very obvious thing — and now, in hindsight, it’s so ridiculous, but this is really the truth. Even The Beatles and Moody Blues and Bob Dylan, all these people, they were all men. And then the people that I started discovering, a lot of them, who were more modern maybe, like Jeff Buckley or Rufus Wainwright, were also men. It really took me a very long time to figure out that women could write songs and were allowed to write songs. And it just did not enter my mind to try. [What changed] was coming in contact with, basically, other girls my age, when I was fifteen and sixteen, who were listening to Ani DiFranco and Tori Amos. It was really those two people: Ani DiFranco and Tori Amos. And I was like, “Oh, they’re writing songs!” And then this friend of mine I met on a trip, on a creative-teenagers trip to Israel that I took, she sent me a cassette tape of Joni Mitchell, and that really... I think that was like...

So the answer is: yes, definitely. But that really blew my mind. And it was like — what’s that called, like, a “triumvirate”?

Yeah, big three.

Yeah, the big three [DiFranco, Amos, Mitchell]. It really made me feel like, “Oh, I should try and write songs.” Because I was also singing a cappella to myself, just in the shower — and in life, I was always humming. But it never entered my mind, because piano, and classical piano, was so sacred to me. And it was also so beautiful. You don’t really want to go from playing beautiful music to your weird oompah-oompah basic stuff. And it was a pretty painful transition, because you kind of go from playing the best music to the worst music.

‘It took me so long to even figure out that I could write songs.’

Until you can make it better.

Yeah, and then you really try to make it better.

Do you do your own background vocals, as well?

Yeah.

Is that part of the puzzle for you? Or is that something, once the Jell-O is gelling, like, “Okay, maybe a third under here.” No?

Never. It’s funny: the songs are the songs, and the songs, the way that I write them, they could be played for people. They’re meant to be “I’ve written this thing, and now I can play it to you in a room and it exists.” And it doesn’t necessarily need the studio to help you feel it, or a band, or anything else. Some people’s music, it lives in an atmosphere. It’s like a vibe or it has to be built. I have plenty of people whose music I love so much, and sometimes the experience is that somebody asks them to play a song, and it’s really hard for them to figure out how to do it, because they need this whole thing to play a song. And I feel like, for the most part, the way that I write the songs, I could play you the song. I might hear a lot of things in my head that you can’t hear, that supplement it, but I don’t need them.

So you feel your songs can be arranged in many different ways.

Exactly. Well, this is part of the mystery of making the records.

A-ha.

All those things, like harmonies and everything, come in with the record-making. When I make the record, then this other weird thing happens where the Jell-O then gets put into another layer of Jell-O, and then that Jell-O has to harden. Because I’m always searching for these things that are only in my head. But they’re also really, really abstract. Because, you know — okay, you compose music — so you could hear a certain kind of thing in your head, and then you go to a real instrument that’s in real space, that’s made of real things, and you touch your finger to a note. And that’s like somebody waking you from a dream, right? It takes you out of these mysterious sounds that are in your imagination, that are outside of real —

It’s like you have to go from the blueprint to actually building something in life.

Right. And then a Steinway brings with it its own thing. If you compose on different pianos, you’re going to make it play different things, because they have their own stuff that they’re. . . It’s like they have their own agenda, and they’re trying to get it out through you. You think you’re playing the piano; the piano is like, “I’m going to play you a little bit!” And same thing with guitar, same thing with everything. And then, it depends on what room you’re doing it in, because the room has its agenda, and then the time of day has its agenda. What midnight’s going to want you to play is different than what nine a.m. is going to want you to play. And so you’re interacting with all these things, and you’re still trying to say something that’s genuine and what you actually want to do, and find the sound for it.

‘You think you’re playing the piano; the piano is like, “I’m going to play you a little bit!” ’

In the studio, it’s really mysterious to me because a lot of the time I end up taking things off of pianos. Because while I’m the happiest performing it live on the piano, the way that I’m trying

to do the source material — the biblical, O.G., this is The Source — the piano might be too specific a sound. Then I have to take it off the piano and put it onto something else. I have to find that something else. So all of a sudden, I find myself cooking a sound. I’m maybe processing the piano, or blending it with the cello, or with a synth, just so, and tucking the synth really subliminally under to create a certain kind of depth

or shadowing. I guess it’s like painting, where you’re like, “You know what? This letter really needs a drop-shadow on it to pop.” Or you put something there, and you put it on a synth, and you do all that stuff, and then you’re like, “You know what? Screw it, it just needs a piano.” [Laughs.]

Is the record the culmination of the song, or is it just a snapshot of the song at that point in time?

Yeah, the second. I kind of wish it was the culmination of the song.

So you could leave it alone —

So I could just rest easy! But the real truth that I have to live with is that there is no real record of any of the songs. And so I just do the best I can at the time. And a lot of the time, I’ll feel really strongly about things being just so, and it’ll be a very particular snapshot. Some of them I’m more happy with, some of them I’m less happy with. But none of them, when I look back, are exactly the same — no matter how hard I work.

Photos: Shervin Lainez, Getty

Keep Listening...

-

Soundboard — Kris Davis

Jazz pianist and Steinway Artist Kris Davis takes us through her process, her love of Herbie Hancock, and what she gained from listening to other instruments.

Read More -

Soundboard — Yulianna Avdeeva

Chopin International Piano Competition winner and Steinway Artist Yulianna Avdeeva discusses her most recent recording project for Pentatone: Dmitri Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87.

Read More -

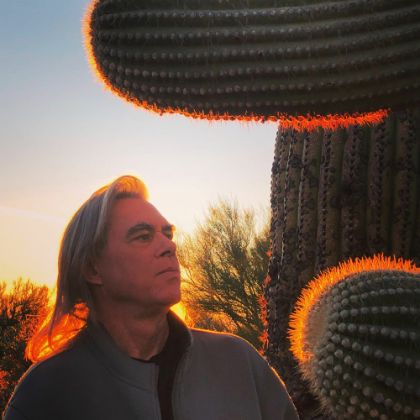

Soundboard — Steve Roach

Ambient and electronic music composer Steve Roach discusses his musical philosophy and process.

Read More -

Soundboard — Sunny War

The songwriter Sunny War talks about her eclectic influences, when less is more, her Americana dream, and taking inspiration from her racist neighbors.

Read More -

Soundboard — Nels Cline

Guitarist Nels Cline, live from Big Ears Festival, talks about having no fixed voice, Wilco, pretension, and going down with the set list.

Read More -

Soundboard — Joe Lovano

Saxophonist Joe Lovano discusses influence, tone, sound, improvisation — and what's in a name.

Read More -

Soundboard — John Paul Jones

Steinway Artist John Paul Jones, live from Big Ears Festival, talks about his influences, his sound, his process and his myriad music projects beyond Led Zeppelin.

Read More -

Soundboard — Christian McBride

Jazz bassist Christian McBride, live from Big Ears Festival, talks post-bop, remaining a bass-player-for-hire, bass-on-bass action, preparation, and jazz as democracy. Steinway & Sons is a sponsor of Jazz House Kids.

Read More -

Soundboard — Jason Moran

Jazz pianist and Steinway Artist Jason Moran, live from Big Ears Festival, talks hip hop, the next generation, the algorithm, Monk & Duke, visual art, and creative approach.

Read More -

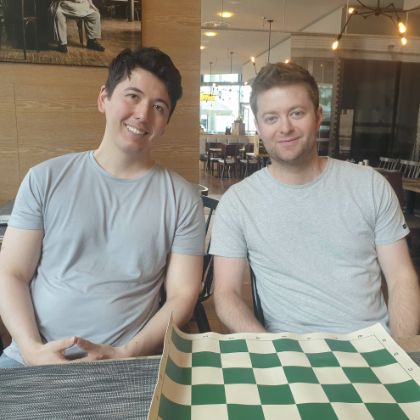

Soundboard — Chessbrah

Eric Hansen and Aman Hambleton, aka Chessbrah, talk techno and chess and what makes Magnus Carlsen the GOAT.

Read More