Listen Magazine Feature

Murray Perahia Discusses The Pull Of Bach, The Invention Of Haydn, His Love For Mozart, Editing The Beethoven Sonatas, The Influence Of Heinrich Schenker, and The Importance Of Rubato.

By Ben Finane

Photo: Felix Broede

MURRAY PERAHIA LIVES in London, and his clean playing recalls the transparency of the great European pianists like Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Maurizio Pollini, to name only two. But the Bronx native’s lyrical, conversational phrasing at the keyboard, his calm command of scale and human sense of time all color his playing with a warmth that is distinctly American and earn him, in my estimation, the designation of our nation’s greatest living pianist. The first North American to win first prize at the Leeds Piano Competition (in 1972), Perahia became both a superior solo and chamber pianist. He spent formative summers in Marlboro, Vermont, where he was encouraged by Rudolf Serkin and collaborated with Pablo Casals and members of the Budapest Quartet. He remains the principal guest conductor of Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Vladimir Horowitz was a crucial confidant and influence in his development as a pianist, while the theories of Heinrich Schenker shaped Perahia as a musical thinker. At his home in London, the pianist was summoned from the keyboard by the phone to speak to Listen. As readers will discover below, Perahia’s phrasing is as expansive as his musical phrasing.

Some prominent musicians I’ve interviewed for Listen champion modern and contemporary music. But I think it’s fair to say that you remain a champion for tonality.

Yes [laughs], — actually, reluctantly. I used to listen to a lot and was a champion of contemporary music at a certain time, but the more that I understood tonally based pieces, the more I went into that world specifically and almost hit a wall with the rest because I just couldn’t understand it; I was... unclear about it. So more and more I understood — and I think correctly — that Bach and all of that is dependent on understanding tonality. To understand Bach, it’s essential to understand dissonance and consonance and how it works. And when you give that up, you lose your bearings, I feel.

I imagine there are many who — having hundreds of years of musical progress and innovation at their disposal — find themselves returning To Bach.

At least I do. Again, this is the path I took — maybe it’s wrong. I’m not saying that there aren’t very important musicians working in contemporary music — and they’re not silly, they’re interesting and intelligent people. But it’s not a way that I can follow because I needed the reference points of tonality in order to understand my work.

Could you discuss tackling the Goldberg Variations? Gould has, perhaps, a higher-profile recording, but I found yours to be so warm and transparent —

Thank you very much. It was a project for many years in my life, but first I decided to tackle the English Suites. I had played a few French Suites, I had played some of The Well-Tempered, I had played the Partitas after a concentrated look at the English Suites — wherein I started working on the harpsichord with a harpsichordist; I had a teacher. And I worked very carefully on how to present these pieces on the harpsichord in order, not to play it on the harpsichord, but to see what expressive devices could be used on the piano from that experience.

And one of the strangest things was — which I didn’t expect — but on the harpsichord, the decay of the sound is not immediate. In some ways, the translation of that [decay] in recordings got a misapprehension and everything sounded detached. Because it was very closely miked, the harpsichord, when it was recorded, and so you had the feeling of ‘tack-tack-tack-tack-tack.’ But actually when you play the harpsichord, that’s the first thing that you feel is the overhang, and that was more reminiscent of [sustain] pedal, on the piano: the piano cannot do that except with a little bit of pedal. And so therefore I started to reassess the use of the pedal in Bach. When I was studying it was considered wrong to use the pedal, and now I’m convinced that it’s very much in the spirit and style of the[se] composers to leave a little bit of harmony overhanging, and the pedal sometimes — not always, obviously, but occasionally — is necessary, in order to make phrasing a little bit less abrupt. And it was expected during that time [the Baroque period] that a little bit of sound would overhang.

Anyway, after working on the harpsichord I decided then to actually go through the Goldberg Variations, and then it wasn’t until after about two years’ worth of work — not continuously, but in the summers, mainly, I would just work on the Goldbergs — and after two years I decided to play it and then to record it.

Photo: Nana Watanabe

Photo: Felix Broede

I find this evolution with the pedal fascinating. Do you take pedaling on a composer-to-composer basis?

Oh yes, very much. For instance, I feel — almost instinctually — that Brahms needs more pedaling, to get those warm sonorities. And Chopin, I feel it’s very important to study his pedalings, because they’re very unusual and they blend harmonies at certain points and then not at other points. So I think a study of Chopin’s pedaling is essential to Chopin.

And I think because the instruments in Mozart’s day [the Classical period] didn’t have an overhang, had an escapement more clear, therefore I would use a little less pedaling in Mozart — of course, a certain amount, because it comes with the piano, but not as much as, let’s say, Beethoven.

Now speaking of Mozart, when I think of your playing — as I said, transparency and warmth — I think naturally of the music of Mozart. And with all the work you did with his concertos [with The English Chamber Orchestra On Sony Classical], it seems a natural fit, the two of you.

Well that’s very kind, thank you. I love Mozart. It never dims, my love of Mozart. No matter where I am with Bach — and I love Bach as well — I’ve always maintained this love of Mozart, and it’s exactly the reason that you said: personal warmth. I think that he understands people and loves people despite the disappointments and whatever. You can see it in all the operas, that somehow all the characters, no matter how bad or difficult they are — or impossible, really — that there is a love that Mozart has for them, a vivacity of spirit, constant in his music whether it’s programmatic, whether it’s for the stage, or whether it’s for the concert hall.

You’ve said that musicians should ‘try to understand music from the inside rather than from the outside.’ And I’ve noticed that you take an interest in the analytical work of Heinrich Schenker, who seems to see music as layers of an onion, with integral parts, and with more fundamental layers underneath —

Yeah, I never thought of an onion, but yes, there is a foreground and there is background and there’s a middle ground in Schenker. And those are three very important concepts. And his graphs deal mainly with the middle ground. Because the background, he feels, is pretty much the same for all music — which is a very startling comment; it’s a very difficult concept to understand and I wouldn’t propose to explain it in five minutes or something like that.

He takes the motto of Goethe: ‘Everything the same, but always in a different way.’ In other words, all nature, all humans work somewhat in the same way, but always different, always it manifests itself always differently. So every piece, according to Schenker, would have similar backgrounds, but it would be the middle ground that would determine a lot of what the piece is, and the foreground is an expression of that middle ground.

What it basically takes away, I think, is this idea that every note is important. There are some notes that are more important and the direction is more important than the notes together, and that there are somehow forces underneath the notes that determine the emotions and also the direction of the piece.

‘There are some notes that are more important, and the direction is more important than the notes together, and there are somehow forces underneath the notes that determine the emotions and also the direction of the piece.’

So what appeals to you about that approach?

It’s not what it seems. [Laughs.] It’s not what it seems on the surface, that there are layers of comprehension. That somehow, this allows you to see a totality, the way the composers said they saw the whole piece — which they had to [have seen], otherwise it would be a collection of this bit and that bit and the other bit, and that’s not the way music is: it has an organic whole. And this allows you to see that, because once you peel away layers of the foreground, you can see basic chords in the middle ground and direct the whole thing. And it becomes simpler for you to understand and you can keep it in your mind.

I have the Schenker–edited Dover Edition Of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas, and now I see you’re editing The Beethoven Urtext manuscripts. So in a way it seems you’re following in Schenker’s Footsteps.

That’s nice of you to say that. I think so, somehow. [Laughs]. Inadvertently, yes, I’m retracing his footsteps through history — in that.

What does that entail, editing An Urtext?

It’s fascinating. I’ve really loved doing it. What I get, before we have the meetings with the editor, is all of the facsimiles of extant autographs, which in the sonatas I think is only about ten out of thirty-two, it’s not so much; so therefore, I’ve insisted on sketches, all of the sketches that the composer did, to determine notes and meanings and... just how he saw the evolution of the piece. So I see all of that plus the first edition before I have long talks with the editor to decide how our edition is going to look and what it will do. And one of the things we’ve tried to do is to re-create the phrasing of the manuscripts where phrase ends are not quite so clear — they seem to go to the next phrase. We tried to do that in certain crucial places in the Beethoven Sonatas. Also, we’re very careful about notes and things — we found some different ones, different dynamic shadings. I guess every editor is going to see different things in the material — anyway, it’s quite a fascinating endeavor and I really love it.

And then there are the fingerings!

Yes!

Are the fingerings you select related to, for lack of a better term, the more important notes, which are going to be played with more important fingers?

Yes, exactly, and the fingering will somehow reveal the phrasing, will be in partnership with the phrasing — so not for security or for ease only, although ease is important to some extent. The main thing is to indicate the phrasing with the fingerings, and that’s what I try to do.

‘It's very important that the technique always be at the surface of the music and, therefore, always to expand one's horizons both technically and musically.’

Five and a half minutes into the first movement of your recording of Bach’s Keyboard Concerto No. 1 In D minor with Academy of St Martin In The Fields comes a remarkably sustained phrase of descending suspensions. Do you know what I’m referring to?

No, I can’t think of it off-hand.

Fortunate, then, that I have it cued up here: [plays first movement Of BWV 1052 (Sony Classical) 5'32"–6'03"] — and then the strings and continuo return. There’s something remarkable about how that phrase — this music — seemingly lives on the edge of disaster. It’s being propelled forward. You’re on the same page with St Martin. It’s a great example of how chamber music, which can sometimes have this unfortunate connotation of powdered wigs and severity, can just be so exciting — this realization of horizontal movement.

Yes, I really appreciate that and I really appreciate your use of the word ‘suspension,’ because they are suspensions, absolutely, and people don’t listen always to the music — we like that.

To me, it speaks to this sense of rubato that you —

— yes —

— and that’s not always done with Bach. I’ve heard you speak about notes inégales rubato, but this is something a little more, with a bit more variation and pull and push.

It’s true. I feel music is always rhythmically dependent on voice leading. In other words, a rigid rhythm is not going to help the music because it doesn’t help the voice leading. If you have a suspension, you hold back a little until you resolve — it’s complicated. At any rate, the voice leading tends to be reflected in the rubato and therefore I think that there’s always a certain amount of rhythmic freedom. Interesting in that respect that C.P.E. Bach, when asked about rhythmic freedom, said, ‘My father’s music you could play pretty straight, but my music, you can’t play one bar of it straight.’ And I think that’s probably true. You could actually get away with playing [J.S.] Bach straight, because it’s so strong, although I don’t like it totally that way.

You certainly don’t play it straight.

No, I don’t. And Bach playing that I love, like Casals’, is not straight. Landowska is not straight at all. What she does with rubato is just unbelievable. And harpsichordists nowadays! [Gustav] Leonhardt, [Bob] van Asperen — they all play with rubato, it’s just natural to their playing. I think that harpsichord you can’t play completely straight. But at any rate, I think that with C.P.E. Bach, I think that once emotions [are] getting defined and then refined, I feel that even more rubato is demanded, which he himself said. [The Dutch keyboardist Gustav Leonhardt passed away shortly after this interview, in Amsterdam, at the age of eighty-three. — Ed.]

Can you share a significant lesson or epiphany from a teacher in your life that changed the way you heard music?

Well, I would start with Casals saying Bach is always human and that the music involved human emotions. And that was very important to me, because in the Fifties and Sixties one heard performances, especially in German orchestras, that were very straight. And that influenced me. Horowitz telling me that ‘to be more than a virtuoso, first you should be a virtuoso’ and working with me on virtuoso music was also very important to me. I think it’s very important that the technique always be at the surface of the music and, therefore, always to expand one’s horizons both technically and musically. Those were very important lessons. The training I got at Mannes College with Carl Schachter and Felix Salzer was very important in determining how I saw music. So I think all three of those were important influences.

Schachter has, incidentally, written the new preface to Schenker’s Dover Edition.

That’s right.

So it must be nice to feel yourself in a sort of scholarly continuum with your teachers and teachers’ teachers.

Yes, I’m very grateful, actually.

Do you have firm ideas about orchestral performance practice? Could you see yourself conducting a cycle of Mozart Symphonies down the road?

When I work with the Academy of St Martin’s, I always do a symphony with them, as well. And I think we’ve done a lot of the Mozart symphonies — we’ve done 35 (the ‘Haffner’); we’ve done the ‘Linz’ [No. 36]; we’ve done the last three great ones, so, the ‘Prague’ [No. 38] — I get great enjoyment out of the Mozart symphonies. And now we’re doing Haydn symphonies, which are fantastic, absolutely fantastic. So that kind of Classical period is what I do most.

Haydn in the symphonic world can often be overlooked in the wake of larger, more massive symphonists. Perhaps you could talk about why Haydn’s symphonies are appealing.

So inventive! I just did one with young people in Berlin, [at] what they call ‘The Academy’ because these people are going to go on to the Berlin Philharmonic; it’s sort of the training orchestra. And we just did the ‘Oxford’ Symphony [No. 92], and every bar is completely unexpected yet inevitable and it somehow is full of wit, all the time, but this wit is not in any way fey or in any way unnatural — it’s completely what the music speaks and I was just amazed at the inventiveness of it. He uses one motive, let’s say ‘Dee, ba ba ba bum, ba ba ba bum,’ and this is used upside down, long augmentation, diminution, in every way and yet it doesn’t feel intellectual, it’s completely natural and it was great, great fun. I’m amazed at Haydn’s breadth of imagination.

Is there music for solo piano that you haven’t yet tackled that you’d like to give more time to?

Yes, I’d like to study the Diabelli Variations. I spend a little time with them every so often and I would like it prolonged so that maybe I’ll play them, hopefully. And there is one Beethoven sonata that I have not played and that’s the Opus 111. Although, again, I’ve looked at it but I’ve never played it in concert. There’s, wow, [laughs] all sorts of music, there’s a lot of Chopin I still haven’t played, Haydn sonatas, Schumann, there’s so much piano repertoire to look into.

In an interview with Listen, Anne-Sophie Mutter said a problem with young rising musicians is that they don't have a point of view. And Speaking With Arnold Steinhardt yesterday, he said what makes you great is that you have a point of view — and also that no one could ever accuse you of playing to the crowd.

Yeah [laughs], that’s very kind of him. But it’s true, I do have a very strong point of view, again based on my influences, based probably on my studies. It’s Schenkerian in some ways, but it is a point of view, and it does inform a lot of my music decisions.

This article originally appeared in Listen: Life with Music & Culture, Steinway & Sons’ award-winning magazine.

related...

-

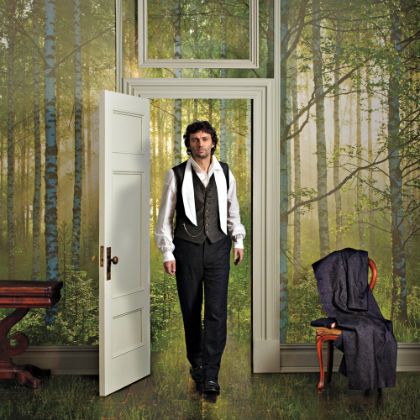

Don't Box Me In

Jonas Kaufmann talks about the evolution of fitness in opera; Parsifal and playing Parsifal; finding an interpretation to suit the composer, director and conductor — and honing it; the essentialness of spontaneity; listening to your body, instinct and doctor; and living on the Five Year Plan.

Read More

By Ben Finane -

An Existential Joy

Thoughts from violinist Leonidas Kavakos on Beethoven and folk music

Read More

By Ben Finane -

Still Singular

Violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter stresses authenticity, dedication and scholarship.

Read More

By Ben Finane